In Conversation with Jane Rothschild of The Anganwadi Project

A ground-up Australian initiative is empowering communities in India that need it the most – through architecture.

According to a 2019 UNICEF report, out of 74 million children in India, in the group of three to six years, around 20 million have no access to pre-school. Most of them belonged to disadvantaged and marginalised sections of society, highlighting the brutal implications of the country’s archaic caste system which, unfortunately, remains in practice, especially in rural areas.

With no access to early education, these children then enter the primary stream with no foundation and thereby creating a continuum of illiteracy and further marginalisation. Notably, it afflicts the South Asian country’s lower-caste populace a lot more in comparison to other poorer sections.

The Indian government first introduced the nationwide concept of Anganwadi (which translates to courtyard shelter in Hindi) in 1975 to address child hunger and malnutrition. It also provides preschool education and basic health services.

Back in 2006, Australian architect Jane Rothschild and costume designer Jodie Fried joined hands to launch a ground-up community initiative called The Anganwadi Project that designs Anganwadi Schools in the Indian states of Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh. What makes these 18 schools stand out from other Anganwadi schools is the fact that Ms Rothschild and her team of volunteers have put people – for whom these facilities have been designed – at the centre of it all. It’s a community project from the start to finish using locally-sourced materials and local building techniques. In an exclusive interview, Ms Rothschild, who was previously the director of Architects Without Frontiers, tells our contributing editor Cara Yap that some of the Australian volunteers have gotten so attached to the project that they ended up staying for over a year because these young architects are passionate about giving back to communities that need it the most and empowering the local people in the process of doing so.

The real success of architecture should not be measured by the awards or accolades it garners, but in the way it serves the people it has been designed for. The Anganwadi Project could be a template for such projects.

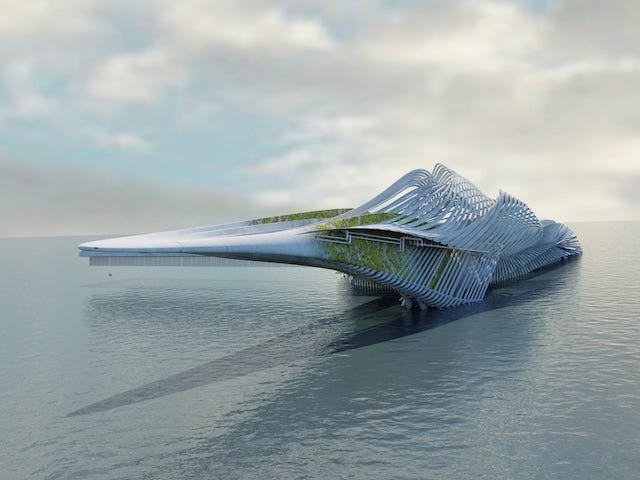

In other news, London-based architect Margot Krasojevic, who has won much praise for exploring the realms of renewable energy and smart agricultural projects, has proposed combined water irrigation and spa system in Nepal (above). The futuristic project aims to contextualise the climate and surroundings while benefitting the local community. But can a project in a natural surrounding that makes itself known rather than be inconspicuous can ever be called contextual? Whose context is it anyway – the site or the architect?

Over in the Middle East, Saudi Arabia continues with its bold ambitions of becoming a major tourism hub in the region. To this effect, it has enlisted the help of its preferred starchitect Lord Norman Foster’s firm Foster + Partners to design yet another high profile project – an airport terminal for an uber-luxury development (above). This comes even as not too long ago, Lord Foster suspended his role in another high profile project – Neom Red Sea development – that created much controversy after the alleged assassination of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi. Memory is short-lived when stakes are high.

In other featured stories, admire the work of Dubai- and India-based design-art studio Apical Reform (below) that captures the current zeitgeist of “Live in the moment” through its acrylic sculptures. And in the Philippines, architect Jim Caumeron has designed an understated yet striking holiday home (above) in Tagaytay town near the Taal Volcano.

We hope you’ll enjoy reading these insightful stories as much as we have enjoyed working on them. If you’d like to provide feedback, tips, or suggestions, we will be delighted to hear from you.

Keep reading and sharing.